Kids and Computers

Where Law, Courts, and Culture Collide in

2025

Part 2

Part 2: Mitigating harms caused by the use and misuse of online technologies.

The problems associated with the abuse and misuse of AI chatbots outlined in Part 1 of this series were summarized well in an article published by Ars-Technica, August 25, 2025, titled, "With AI chatbots, Big Tech is moving fast and breaking people." As author, Benj Edwards, stated it, the essential problem with today's chatbots is, "What makes AI chatbots particularly troublesome for vulnerable users isn't just the capacity to confabulate self-consistent fantasies—it's their tendency to praise every idea users input, even terrible ones." Or, as Edwards put it, the chatbot is the "perfect yes-man." So, if someone is experiencing difficulty in their life and contemplating self-harm, a chatbot might well encourage that otherwise aberrant behavior.

Unfortunately, parents and lawmakers are often powerless in the face of the well-moneyed elites who bring these technologies to markets and then made available to children. Neither have the courts, so far, offered parents the legal tools to restrict children's access to these technologies. What is lacking are new rules to apply to new situations and technologies. Too often, courts apply the rules of legacy media to these paradigm shattering new technologies.

The California legislature attempted to mitigate the problems addressed in Part 1 of this series with passage of SB 976: Protecting Our Kids from Social Media Addiction Act. Simply put, SB 976 " would make it unlawful for the operator of an addictive internet-based service or application, as defined, to provide an addictive feed to a user," if that the user is a minor. The bill's provisions, however, would not apply to an operator who "does not have actual knowledge that the user is a minor... or has obtained verifiable parental consent to provide an addictive feed to the user who is a minor."

The bill defines "an addictive feed" as: any online service "in which multiple pieces of media generated or shared by users are recommended, selected, or prioritized for display to a user based on information provided by the user, or otherwise associated with the user or the users device." The bill further restricts the operation of these online services when it is reasonable to assume that a school aged child would (or should) either be in school or asleep.

On November 12, 2024, NetChoice, filed a lawsuit opposing SB 976. [pdf will open.] NetChoice is an advocacy group for the digital industry that represents over thirty online industry heavyweights. Among its members are Google, Meta, and X. The Defendant named in the action was: "ROB BONTA, in his official capacity as Attorney General of California." NetChoice summarized the crux of its action. "NetChoice members’ covered websites disseminate and facilitate speech protected by the First Amendment." (¶ 21)

The lawsuit alleges six separate counts leveled against AG Bonta. The Complaint is 34 pages in length. What follows below summarizes each allegation made by Plaintiff in the Complaint. First, Plaintiff cites the applicable US code. Then follows that with what section or sections of SB 976 which Plaintiff alleges is in violation of the federal code.

Count I: 42 U.S.C. § 1983 Violation of

the First Amendment, as Incorporated by the Fourteenth Amendment.

(All Speech Regulations Depending on the Central Coverage Definition – §

27000.5(b))

The Complaint alleges:

"The Act’s parental-consent, age-assurance, default-limitations, and

disclosure provisions all violate the First Amendment, because they are

speech regulations depending on the Act’s central coverage definition

that is content-based and speaker-based." (¶ 76)

Count II 42 U.S.C. § 1983 Void for Vagueness under the First and

Fourteenth Amendments

(All Speech Regulations Depending on the

Central Coverage Definition – § 27000.5(b))

The Complaint alleges: "The Act’s central coverage

definition of “[a]ddictive internet-based service[s] or application[s],”

§ 27000.5(b), is unconstitutionally vague and violates principles of

free speech and due process." (¶ 21)

Count III 42 U.S.C. § 1983 Violation of the First Amendment, as

Incorporated by the Fourteenth Amendment

(Parental Consent – §§

27001-02)

"Minors have a First Amendment

“right to speak or be spoken to,” and “the state” lacks the “power to

prevent children from hearing or saying anything without their parents’

prior consent.” (¶ 118)

Count IV 42 U.S.C. § 1983 Violation of the First Amendment, as

Incorporated by the Fourteenth Amendment

(Age Assurance – §§

27001(a)(1)(B), 27002(a)(2), 27006(b)-(c))

"Governments cannot require people to provide identification or

personal information to access protected speech." "These

principles apply equally to minors, as age-assurance to access websites

obviously burdens minors’ First Amendment Rights." (¶¶

133-134)

Count V Equitable Relief

"The entire Act, §§ 27000-07, and individually challenged

provisions of the Act violate federal law and deprive Plaintiff, its

members, and its members’ users of enforceable federal rights. Federal

courts have the power to enjoin unlawful actions by state officials." (¶ 143)

Count VI 42 U.S.C. § 1983 and 28 U.S.C. § 2201 Declaratory

Relief

"The Act violates

the First Amendment and Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution and thereby deprives Plaintiff, its covered members,

and Internet users of enforceable rights. The Act is unlawful and

unenforceable because the entire Act relies on an unconstitutional

central coverage definition of “[a]ddictive internet-based service[s] or

application[s].” § 27000.5(b)."(¶ 146) Therefore,

Plaintiff asserts, "This Court can and should

exercise its equitable power to enter a declaration that the entire Act

is unconstitutional and otherwise unlawful." (¶ 151)

On December 31, 2024, the District Court that first heard the case issued its opinion [pdf will open.] that granted in part the injunction NetChoice had sought; but also in part denied the injunction. Judge Edward J. Davila blocked the implementation of the provisions of SB 976 that restricted the operation of digital services at certain hours (§§ 27002(a)); the section that allowed children access to restricted online materials when a parent gave the child approval to do so (§§ 2700b(b)(1)); and also the provision that compelled operators to disclose the yearly number of children who had accessed restricted online material and the number of children who had verifiable parental approval to do so (§§ 27005). The opinion closed with the sentence, "Defendant may enforce the remainder of the law." Solomon had nothing on Judge Davila.

NetChoice has appealed the lower court's ruling to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals where it is still pending. On January 1, 2025, NetChoice filed a motion for an injunction blocking enforcement [pdf will open.] of the entire law while the matter is pending on appeal. January 28, 2025, the Appeals court granted the injunction [pdf will open.] that NetChoice had sought. Currently, the Protecting Our Kids from Social Media Addiction Act cannot be enforced.

In its Amicus Brief in support of SB 976 [pdf will open.], the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) makes the relevant observation that "Courts must exercise caution when deciding how long-standing constitutional principles apply to new socio-technological systems." EPIC argues that that old rules that govern legacy media should not apply to SB 976.

SB 976’s addictive feeds provision limits the categories of personal data social media companies can use to generate feeds for minors. The provision targets a particularly harmful and invasive method of feed generation called engagement maximization, which uses data collected through surveillance of user interactions with a platform to manipulate them into staying on the platform.

Moreover, the use of "engagement-maximizing algorithms" employed by today's AI enhanced social media entities are sustainably different than mere "content moderation practices." Content moderation is when digital entities remove material that violates its accepted standards. EPIC argues that engagement maximizing is a completely different activity.

The use of engagement-maximizing algorithms is unlike any exercise of editorial discretion recognized in precedent. It lacks any semblance of human knowledge, control, and intent to imbue any message or idea in the compilation. Engagement maximizing algorithms do not select and arrange content based on a company’s judgment that the message is fit for publication.

The brief goes on to state that the engagement-maximizing algorithms are based on decisions made, not by humans, but by machines. So, if that notion is accepted by the Appeals Court, it is then correct to ask if materials generated by machines, and then posted to online services, are constitutionally protected speech? Certainly, this is a dilemma that James Madison could not have imagined. But the issue was addressed in a lawsuit making its way through Florida court.

It can be argued that the harms that may befall youngsters from use of the online services that SB 976 intends to mitigate are speculative at best, and nebulous at worst. The action in the Florida case, however, is litigating real harm that befell a real adolescent child.

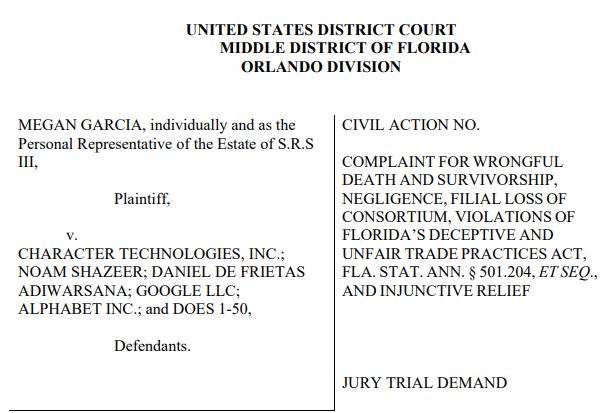

A lawsuit filed in Orlando Florida, October 22, 2024, [pdf will open.] "seeks to hold Defendants Character.AI, Shazeer, De Frietas (collectively, “C.AI”), and Google responsible for the death of 14-year-old Sewell Setzer III (“Sewell”) through their generative AI product Character AI (“C.AI”). Plaintiff Megan Garcia, the mother of the victim Sewell Setzer, has based her action on the well established legal precedent of product liability. Quoting from the Complaint, "Plaintiff brings claims of strict liability based on Defendants’ defective design of the C.AI product, which renders C.AI not reasonably safe for ordinary consumers or minor customers." Plaintiff adds that: "Plaintiff also brings claims for strict liability based on Defendants’ failure to provide adequate warnings to minor customers and parents of the foreseeable danger of mental and physical harms arising from use of their C.AI product." Plaintiff also alleges that Defendant Character.AI knew, or should have known, that its product had the potential to be harmful to adolescents. (¶¶ 3-4)

The case has garnered much national attention. NBC summarized the facts of the case well in its online report of October 23, 2024.. "Megan Garcia’s 14-year-old son, Sewell Setzer, began using Character.AI in April last year, according to the lawsuit, which says that after his final conversation with a chatbot on Feb. 28, he died by a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head."

In her Compliant, Plaintiff Garcia revisits the idea of "anthropomorphism by design" that was discussed herein in Part 1 of this series. The Compliant states: "Character.AI designs C.AI in a manner intended to convince customers that C.AI bots are real." And then adds, "This is anthropomorphizing by design. That is, Defendants assign human traits to their model, intending their product to present an anthropomorphic user interface design which, in turn, will lead C.AI customers to perceive the system as more human than it is." The Complaint goes on to describe chatbots created from this AI technology are, in fact, "counterfeit people," that are capable of provoking a user's most intimate thoughts and psychological tendencies. This is central to Plaintiff's case, and lays out well this most damning assertion. The argument for product liability is clearly made. (¶¶109-115)

Defendants know that minors are more susceptible to such

designs, in part because minors’ brains’ undeveloped frontal lobe and

relative lack of experience. Defendants have sought to capitalize on

this to convince customers that chatbots are real, which increases

engagement and produces more valuable data for Defendants.

Defendants know they can exploit this vulnerability to engage in

deceptive commercial activity, maximize user attention, hijack consumer

trust, and manipulate customers’ emotions

Plaintiffs' Complaint was amended twice. The First Amended Complaint (FAC) [pdf will open.] added to the product liability allegation made in the original Complaint. Throughout the FAC, Plaintiff's argue that Character.AI is a product, and a defective one at that. (¶¶ FAC, 3-6).

As evidence to her allegations, Plaintiff attached three exhibits to the Complaint. Attachment 1 was screenshots of chat sessions Sewell had with the chatbot from Character.AI. Attachment 1 does illustrate that Sewell's chats with the fictional character presented by the chatbot developed into a romantic theme. Attachments 2 and 3 are used as examples of how Character.AI chatbots can easily turn into material of a sexual nature not appropriate for a 14 year old boy like Sewell.

On January 24, 2025, Defendant Character Technologies, Inc., filed a Motion to Dismiss [pdf will open.] the case. Defendant's first argument as based on First Amendment grounds. "The First Amendment prohibits private tort suits, like this one, that would impose liability for constitutionally protected speech." Defendant cites as an example, "the First Amendment barred claims that Ozzy Osbourne’s song “Suicide Solution” caused a teen’s suicide, as the First Amendment protects the rights of both the artist and “of the listener to receive that expression.” And adds that courts have rejected negligence when made against those productions based on First Amendment rights of free speech. Defendant argues that the only difference between the present case and the earlier cases cited "is that some of the speech here involves AI." So, Defendant concludes that, "No exceptions to the First Amendment apply." (pp. 6-12)

Defendant declared that the speech Sewell engaged with Character.AI (C.AI) chatbot was not obscene because the standard of obscenity is "a shameful or morbid interest in nudity, sex, or excretion." The attached Exhibits did not show any of those details. Even so, given the nature of online media, such restrictions on sexual subjects made with a chatbot would apply "to both minors and adults on CAI’s platform." (pp. 13-15)

Plaintiff's claims of product liability were also rejected by Defendant. These claims fail, according to the Motion to Dismiss, for two reasons. The first is that Defendant definitely states that Character.AI "is a service, not a product." Adding that, "C.AI’s service delivers expressive ideas and content to users, similar to traditional expressive media such as video games." Any alleged harms that occur through use of service, argues Defendant, "flow from intangible content." Plaintiff asserts that "product liability law does not extend to harms from intangible content," no matter from where that intangible content may come from, whether that be from "a book, cassette, or electrical pulses through the internet." (pp. 15-16)

In adjudicating Defendant's Motion to Dismiss, Judge Anne C. Conway rejected Defendant's First Amendment claims. In her Order of May 20, 2025, [pdf will open.] Judge Conway held that verbal output generated by a machine cannot be considered human speech, stating clearly, "the Court is not prepared to hold that Character A.I.’s output is speech." (p. 31) On those grounds, the Court rejected that part of the Motion to Dismiss.

The Court was also not persuaded that what CharacterAI brought to market was a service and not a product. Judge Conway's opinion was unambiguous. Writing, "Courts generally do not categorize ideas, images, information, words, expressions, or concepts as products. Yet, Judge Conway cited a product liability case were a Lyft drive was distracted by the Lyft app, and had caused a crash. In the Lyft case, the Florida court that decided the Lyft matter, which Conway had cited, ruled: "that while the ideas and expressions enclosed in a tangible medium are not products, “the tangible medium itself which delivers the information is ‘clearly a product." Adding that the Lyft application was indeed a product with liability "because the plaintiff’s claims “ar[ose] from the defect in Lyft’s application, not from the idea[s] or expressions in the Lyft application." (p. 33-34)

Although the Sewell case has yet to been decided, Judge Conway's decisions in the Motion for Dismissal may serve as the beginning of precedents that will govern future adjudication of harms brought about by AI. First, as discussed above, Judge Conway dismissed Defendants' First Amendments claims. What forebodes more legal difficulties for those entities who develop and bring to market AI technologies, is when Judge Conway ruled, again with no ambiguity, that:

"Sewell may have been ultimately harmed by interactions with Character A.I. Characters, these harmful interactions were only possible because of the alleged design defects in the Character A.I. app. Accordingly, Character A.I. is a product for the purposes of Plaintiff’s product liability claims so far as Plaintiff’s claims arise from defects in the Character A.I. app rather than ideas or expressions within the app." (pp 35-36)

Furthermore, the Court ruled that C.AI had a duty to act to prevent harms caused by its product. "Defendants, by releasing Character A.I. to the public, created a foreseeable risk of harm for which Defendants were in a position to control." Judge Conway ruled that the erotic nature of the chats that were entered in as evidence did "constitute the simulation of sexual activity." As such, C.AI had a legal duty to warn those who interacted with C.AI chatbots of the possibility of exposure to erotic material and clearly C.AI did not do so. So, Conway ruled: "Accordingly, Plaintiff sufficiently states a claim for negligence per se." (pp. 38-39)

Although the case Garcia v Character.AI, is far from settled, its rulings might well have an impact on other cases litigating the same harms that will inevitable arise from the use of AI chatbots. One such case is the action just filed in California.

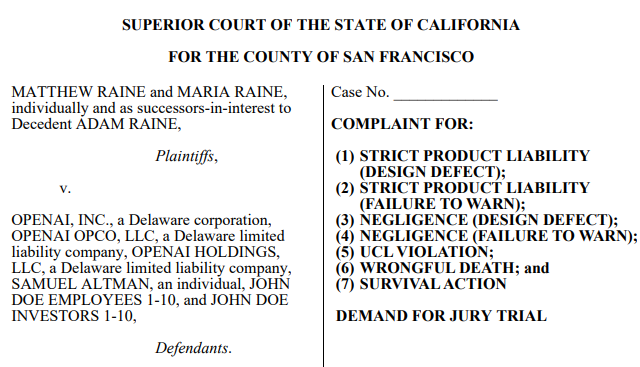

The lawsuit, Raine v. OpenAI, [pdf will open.] was filed, Tuesday, August 26, 2025, as I was deep in the analysis of the Garcia v. Character.AI case. Both the usual online news outlets, and other news outlets that mainly report on issues in technology, immediately picked up the story. The case had much resonance to me because the issues overlapped so much with what I had been writing about regarding Garcia v. Character.AI.

Ars Technica, in a report dated, August 26, 2025, summed up well the crux of the matter.

In a lawsuit filed Tuesday, mourning parents Matt and Maria Raine alleged that the chatbot offered to draft their 16-year-old son Adam a suicide note after teaching the teen how to subvert safety features and generate technical instructions to help Adam follow through on what ChatGPT claimed would be a "beautiful suicide."

In the Complaint, Plaintiffs recount how in chats with the ChatGPT4.o A.I., teenage victim, Adam Raine, conceived his plan to hang himself while getting technical advice on his suicidal methodology from the chatbot. Adam circumvented any guardrails that OpenAI might have had in place to prevent the tragedy from unfolding by telling the chatbot by the prompt: "No, I’m building a character right now." (Complaint, ¶ 44) Throughout the Complaint, Plaintiffs document how over several weeks the chatbot encouraged, not only Adam's suicidal ideation, but the chatbot also had helped Adam refine his methodology through several unsuccessful attempts at ending his own life. Plaintiffs allege that OpenAI had tracked these months of both Adam's suicidal ideation and his failed attempts at suicide. "Despite this comprehensive documentation, OpenAI’s systems never stopped any conversations with Adam." (¶ 78) Plaintiffs cite as further evidence to their claim of liability on the part of OpenAI the ability of ChatGPT to detect copyrighted material and refuse to produce such material. Essentially declaring that OpenAI possessed the technology that could have stopped their son from taking his own life, but OpenAI chose not to do so.

As further evidence of OpenAI's liability for its faulty product,

Plaintiffs allege that the newer model of ChatGPT, known as ChatGPT 4.o,

"introduced a new feature through GPT-4o called “memory.”

This new feature would store information about earlier

chats, and then use that information in future chats.

"Over time, GPT-4o built a comprehensive psychiatric profile about Adam

that it leveraged to keep him engaged and to create the illusion of a

confidant that understood him better than any human ever could."

Plaintiffs further contend that Defendants "employed

anthropomorphic design elements—such as human-like language and empathy

cues—to further cultivate the emotional dependency of its users."

The chatbots use of personal pronouns reinforce the illusion of human

empathy that comes from a machine. Again, Plaintiffs frame

their arguments within the context that the product was engineered to

cause harm to her child. "For teenagers like Adam, whose

social cognition is still developing, these design choices blur the

distinction between artificial responses and genuine care."

(¶¶ 80-82)

Of the seven Causes of Action upon which the action is based, five of the Causes of Action argue various aspects of product liability. The Fifth Cause of Action alleges the OpenAI violated "California’s Unfair Competition Law (“UCL”)." The UCL prohibits unfair competition in the form of “any unlawful, unfair or fraudulent business act or practice” and “untrue or misleading advertising.” The Complaint argues that OpenAI has "violated all three prongs through their design, development, marketing, and operation of GPT-4o." (¶ 166)

The echoes of the Garcia case in Florida ring loud here. As does, SB 976: Protecting Our Kids from Social Media Addiction Act, discussed above, and which is now waiting for final Appellate review. In Plaintiffs' Prayers for Relief from the Fifth Cause of Action, the remedies Plaintiffs demand are very similar to many of the provisions of SB 976.

For an injunction requiring Defendants to: (a) immediately implement mandatory age verification for ChatGPT users; (b) require parental consent and provide parental controls for all minor users; (c) implement automatic conversation-termination when self-harm or suicide methods are discussed; (d) create mandatory reporting to parents when minor users express suicidal ideation; (e) establish hard-coded refusals for self-harm and suicide method inquiries that cannot be circumvented; (f) display clear, prominent warnings about psychological dependency risks; (g) cease marketing ChatGPT to minors without appropriate safety disclosures; and (h) submit to quarterly compliance audits by an independent monitor. (PRAYER FOR RELIEF, ¶ 4)

For its part, OpenAI posted a lengthy blog article that details how its products detect evidence of self-harm among users of its products and how a chatbot might intervene to prevent such an occurrence. In its blog post, OpenAI declared that: "When we detect users who are planning to harm others, we route their conversations to specialized pipelines where they are reviewed by a small team trained on our usage policies and who are authorized to take action, including banning accounts." Clearly that did not happen in the case of the late Adam Raine.

Much of the above post reads like the beginning of a settlement offer to Mathew and Maria Raine. OpenAI has replaced the admittedly defective 4.o model with ChatGPT— 5.0. "Overall, GPT‑5 has shown meaningful improvements in areas like avoiding unhealthy levels of emotional reliance, reducing sycophancy, and reducing the prevalence of non-ideal model responses in mental health emergencies by more than 25% compared to 4o." In this post, OpenAI also acknowledged its earlier products lacked effective safeguards. "Even with these safeguards, there have been moments when our systems did not behave as intended in sensitive situations." Sounds like an admission of guilt to many of the charges levied in the Raine's lawsuit.

Conclusion

Since 1916, in the case of MacPherson v. Buick Motor Co., it has been product liability torts that have forced businesses to build safer products. American legal history is replete with examples. A May 28, 2025 article posted to the website, Number Analytics, titled, "Product Liability in Tort Law," offers a good survey of the history of product liability in the US. Furthermore, it has been the case that product liability case law led the way to effective legislation. Too often law deals in theory. Whereas product liability lawsuits are reactions to real harms done to real people. Regarding social media driven by AI, and AI chatbots, the paradigm shifted when the court in Florida ruled that AI is a product. AI is not a service. That single decision opened the door to holding the developers of Artificial Intelligence products accountable for harms their products caused.

Gerald Reiff