Computers In the Classroom

A Classic Case of the

Double Edged Sword

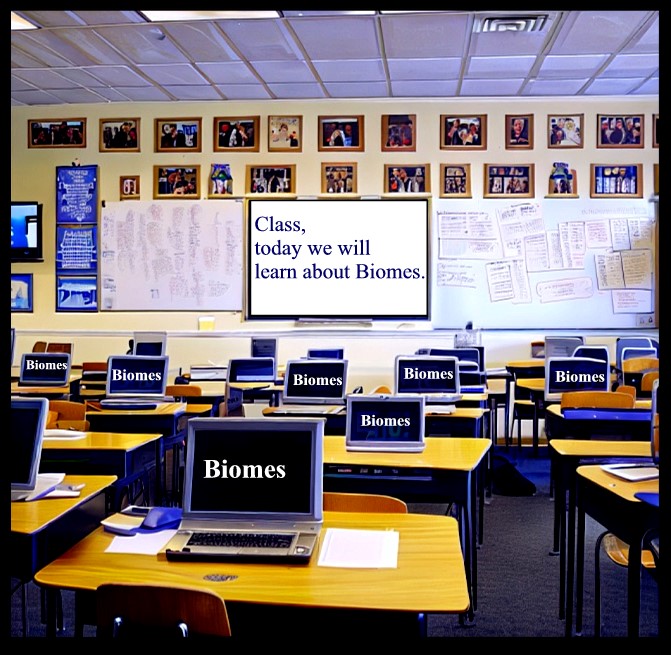

In

Rodney Dangerfield's uproarious 1986 comedy,

Back To School, there was one truly hilarious sight

gag where the protagonist enters a classroom. In the front of

the

class is a large reel to reel tape recorder running. In each seat,

where one expects to find warm young bodies seated taking notes, are

nothing but empty chairs, with a

mini-cassette recorder on the desk of each chair. I found this scene

especially funny because, as a returning adult college student two years

before the film's release, I

was surprised at how many students never took actual notes, but instead

recorded the lectures on cassette recorders. This assumed the

instructor allowed tape recorders in their classrooms. At the time,

a sizable number of college profs would not allow tape recorders in

their classrooms. I can't remember how often I sat through short

lectures about how study after study showed that if a person actually

wrote something down, then they were far more likely to remember what they

wrote. Fast forward to today, and the computer has replaced the

cassette recorder in the toolbox of modern

pedagogy.

(image source:

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0090685/mediaviewer/rm1240112896/)

enters a classroom. In the front of

the

class is a large reel to reel tape recorder running. In each seat,

where one expects to find warm young bodies seated taking notes, are

nothing but empty chairs, with a

mini-cassette recorder on the desk of each chair. I found this scene

especially funny because, as a returning adult college student two years

before the film's release, I

was surprised at how many students never took actual notes, but instead

recorded the lectures on cassette recorders. This assumed the

instructor allowed tape recorders in their classrooms. At the time,

a sizable number of college profs would not allow tape recorders in

their classrooms. I can't remember how often I sat through short

lectures about how study after study showed that if a person actually

wrote something down, then they were far more likely to remember what they

wrote. Fast forward to today, and the computer has replaced the

cassette recorder in the toolbox of modern

pedagogy.

(image source:

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0090685/mediaviewer/rm1240112896/)

Recent news reports concerning education in America have all taken note of declining test scores among American students at all grades. U.S. News, reported in an article dated June 21, 2023, that among American teens, reading scores "were actually lower than the first year the data was collected, in 1971." Math scores were similarly dismal.

The closing of schools brought on by the COVID pandemic is an often cited reason for this precipitous drop is measurable performance among school aged children, not just in the USA, but across all nations in the developed world. As The Guardian noted in an article dated January 17, 2024 that is aptly titled, "A groundbreaking study shows kids learn better on paper, not screens. Now what?," that "the blame for this dismal news has been assigned by politicians to the easiest, more obvious targets – Covid-19 and the resultant lockdown." Yet, in a USA Today report of August 5, 2023, despite substantial increases in the funding of American schools beginning in 2022, not much improvement in test scores among America's kids have yet to be realized. As this comprehensive report on what is actually going on in America's school states:

More than three years after the COVID outbreak began, some children are thriving but many others remain severely behind. This reality means recovering from COVID could be more costly, time-consuming and difficult than they anticipated, leaving a generation of young people struggling to catch up.

The report lists several facts about education in America today that may lie at the root causes of the continuing poor performance of America's school aged kids. The Guardian article noted above, citing the most research into the problems of contemporary pedagogy, points its finger at a different culprit: the now ubiquitous presence of computers in the modern classroom. Like my college profs from the 1980s thought, old fashioned paper still beats out any new fangled labor saving gizmos when it comes to learning. In a very recent study of middle school students made by, "neuroscientists at Columbia University’s Teachers College," as noted in The Guardian article, other problems with how today's kids learn in school were found. COVID wasn't the only culprit.

In its research, the Columbia University study authors made a distinction between "shallow reading" and "deep reading." Quoting from the Abstract of the report, "shallow reading would produce weaker associations between probe words and text passages." In contrast, "deeper reading of expository texts would facilitate stronger associations with subsequently-presented related words." The authors employed the N400 reading standard used by the US Department of Immigration and Naturalization as the foundation for their methodology. The researchers summarized their findings thusly:

Following digital text reading, the N400 response pattern anticipated for shallow reading was observed. Following print reading, the N400 response pattern expected for deeper reading was observed for related and unrelated words, although mean amplitude differences between related and moderately related probe words did not reach significance. These findings provide evidence of differences in brain responses to texts presented in print and digital media, including deeper semantic encoding for print than digital texts.

This certainly flies in the face of the traditional wisdom that governs the use of computers in America's public schools. As author John R MacArthur noted in The Guardian piece cited above, these newest findings have not, as of yet:

... influenced local school boards, such as Houston’s, which keep throwing out printed books and closing libraries in favor of digital teaching programs and Google Chromebooks. Drunk on the magical realism and exaggerated promises of the “digital revolution”, school districts around the country are eagerly converting to computerized test-taking and screen-reading programs at the precise moment when rigorous scientific research is showing that the old-fashioned paper method is better for teaching children how to read.

Now comes Microsoft into the broader discussion of reading, computers, and

pedagogy. An article in

ZDNet, dated Jan. 19, 2024, reports on the tech giant's recent foray

into learning by computer, specifically aimed at improving student's

reading and comprehension. Microsoft has added to its growing mix

of AI powered online technologies, its

Reading Coach. The screenshot below is from

https://coach.microsoft.com/.

On its Support Page for Reading Coach, "Getting started with Reading Coach," Microsoft offers a succinct one paragraph description of its Reading Coach.

Reading Coach is a free tool that provides personalized, engaging, consistent and independent reading fluency practice. Reading Coach uses artificial intelligence and built-in fluency detection to personalize reading content with the words learners struggle with, while ensuring a safe and trusted experience. Reading Coach is available for use in the classroom or at home with a Microsoft account. Reading Coach is currently available in US-English, with support for additional languages and dialects coming in 2024.

The Reading Coach is quite new. And as such, I have not had time to use and evaluate this online resource. Most likely, the Reading Coach will be a topic for a future Dispatch. For now, I simply offer this learning resource to loyal readers of The Dispatches.

Very recently, I have had the opportunity to observe how computers — specifically Chromebooks — are used in an actual Middle School classroom. Certainly, I have no means to evaluate any student's performance before the introduction of Chromebooks in that classroom compared to now. What I have observed is the impact of the computer on students' behavior in the classroom. Here not much has changed. Good students are good students, who will always find their own ways to scholastic success, no matter the obstacles placed in their way. Bad students will always misbehave and waste their own class time, as well of those of teachers and other students.

One obvious problem with Internet connected computers in the classroom is the same problem all computer users experience these days. There are so many ways that having an Internet connected computer can become a distraction. In the classroom I had observed, seated at every table were groups of students with open Chromebooks. At least one student at each table played games while the teacher was speaking. Some had their earbuds plugged in listening to music. Those students who were not following the class often became annoyances to the students in close proximity who did want to pay attention and follow the lesson.

Another problem is the ease in which plagiarism can occur. I worked with one student on a writing assignment, using the connected Chromebook as a research tool. The student wanted to copy and paste text from his source, rather than interpret in his own words the text he had just read. Only minutes before, the teacher commented on how, in another class, students handed in written work that the teacher knew was not written by those students. I had to remind the student I had worked with about the words spoken just minutes before by the teacher. I told him that if you copy and paste, the teacher will know those would not be your words, and that would most likely lower your grade for the assignment.

Undoubtedly, however, the computer in the classroom is a great time and labor saving device for the teacher. She assigned an open book test, using Google Classroom. Teacher put the test material online; students took the exam online; and then the tests were immediately graded by the online test application. Students received immediate feedback in real time on their learning. Textbooks and other printed materials were available in the classroom, but were also available online. Students need not schlep textbooks home anymore. Only having a Chromebook in the backpack, opposed to a collection of bound paper copies of books, probably saves much wear and tear on young backs and spines.

I have maintained for the longest time that the computer is a tool. A tool is an inanimate object. Its usefulness depends on the use humans put to the tool. That maxim of mine certainly applies to the use of computers in the classroom.

In the early 1990s, I left the computer industry and entered graduate school. All of the compositions written in my graduate studies, including my Master's thesis, were written on an IBM PC XT, with a whopping 640kb of RAM and a 20mg hard drive. The word processor I had used was Wordstar 5, running under MS-DOS. My class notes, however, were all hand written into spiral bound notebooks. Each course had its own notebook. My GPA as a grad student was 3.9 — damn that one "B".

In a recent post, I introduced readers of the Dispatches to the free online courses in AI offered by IBM. In discussing the quizzes and exams that must be passed with a score of at least 80% to earn a completion certificate for any class, I suggested that, like in college, the key to success is taking copious notes. Yes, I wrote notes by hand while taking an online course in our newest digital technology, Artificial Intelligence. When it comes to learning, the old tried and true methods still offer the best results.

Gerald Reiff

| Back to Top | ← previous post | next post → |

| If you find this article of value, please help keep the blog going by making a contribution at GoFundMe or Paypal | ||